Paper Trails #15: The Newsprint Revolution — How Black Panther Community Newsletters Recorded a Movement in Real Time

- andrea0568

- Dec 14, 2025

- 4 min read

The Black Panther Party did not set out to create an archive.

They set out to feed children, monitor police, educate neighbors, and survive sustained state repression. The newsletters—mimeographed, offset-printed, folded, stapled, and handed out on street corners—were tools of communication, not monuments. They announced meetings. They explained programs. They corrected rumors. They raised bail money. They told people where to show up and why it mattered. And in doing so, they accidentally documented one of the most complex grassroots political subcultures of the 20th century.

Not a Newspaper—A Nerve System

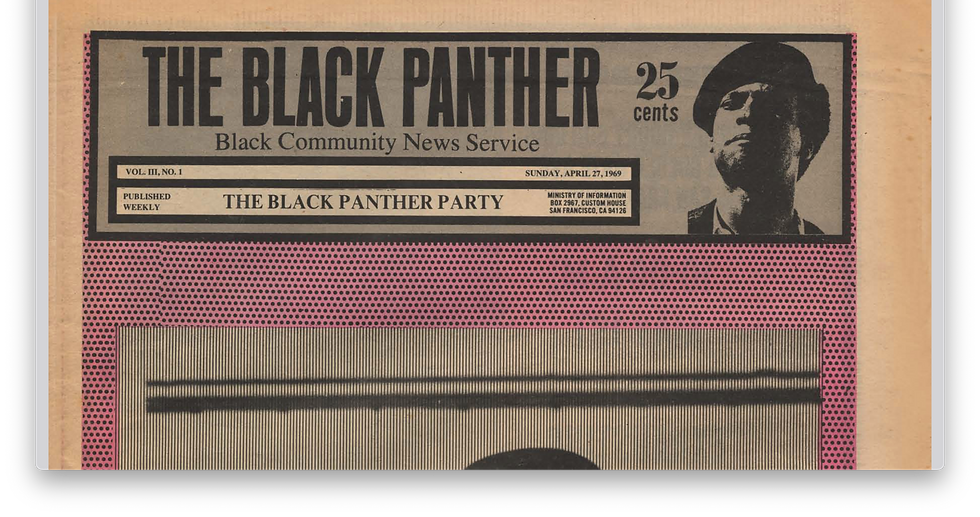

The best-known publication, The Black Panther newspaper (first issued in Oakland in 1967), is often treated as the Party’s official voice. But alongside it existed a dense ecosystem of local and regional community newsletters produced by individual chapters across the United States: Oakland, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, New Haven, and beyond.

These newsletters were not uniform. Some were professionally printed; others were barely held together by staples and hope. What unified them was function. They were internal and external simultaneously—speaking to members, supporters, and curious onlookers in the same breath.

They carried:

Updates on Free Breakfast for Children programs

Notices about health clinics and sickle cell anemia testing

Reports on police encounters and court cases

Obituaries for fallen members

Essays explaining ideology in plain, accessible language

Read today, they feel less like propaganda and more like logistics. This is a movement figuring itself out week by week.

Local Voices, Local Realities

One of the most striking things about Panther newsletters is how regional they are. National rhetoric dissolves quickly when confronted with local needs.

A Chicago chapter newsletter might focus on housing conditions and police surveillance. An Oakland issue might emphasize education programs and party leadership. New York newsletters often grappled with media misrepresentation and internal security. These were not interchangeable chapters—they were communities responding to specific pressures.

That specificity matters. It shows how national movements are built from uneven, local labor. The newsletters preserve the texture of that labor: who was tired, who was angry, who was organizing food drives instead of writing manifestos.

Design as Political Language

Visually, the newsletters are unmistakable. Heavy black ink. Bold headlines. Emory Douglas’s graphics—raised fists, armed figures, children with breakfast plates—reappear across issues, sometimes altered, sometimes reused until the blocks wore thin.

This wasn’t aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake. It was visual literacy. The imagery communicated urgency and solidarity at a glance, especially in communities where access to long-form political texts was limited.

Crucially, these visuals traveled. A newsletter folded into a pocket could cross neighborhoods, cities, and state lines. It could be read aloud. It could be copied. It could be seized—or hidden.

Printed Under Pressure

The survival of these newsletters is inseparable from the conditions under which they were produced.

The Black Panther Party was subjected to extraordinary surveillance and disruption, most infamously through the FBI’s COINTELPRO program. Offices were raided. Printing equipment was confiscated. Distribution networks were deliberately targeted. This made newsletters both vulnerable and vital.

Some issues survive only because someone tucked them away instead of handing them out. Others exist with visible signs of haste—misaligned type, uneven ink, missing pages—evidence of printing under stress.

In archival terms, these imperfections are gold. They show us the cost of speaking publicly when doing so carried real risk.

What These Newsletters Preserve That Speeches Don’t

Speeches tell us what leaders wanted to say. Newsletters tell us what communities needed to do.

They record:

How often programs met

Where money was short

Which initiatives quietly disappeared

How rhetoric shifted after arrests or deaths

What optimism looked like on a bad week

This is not polished history. It is operational history.

And that is precisely why historians, librarians, and archivists now prize these materials. They reveal how ideology translated—or failed to translate—into daily practice.

Accidental Archives of Care and Conflict

It is tempting to read these newsletters solely as political artifacts. But they are also records of care. Lists of food distribution sites. Calls for volunteers. Notices asking neighbors to protect children walking to breakfast programs.

At the same time, they do not hide internal strain. Disagreements surface. Tensions are hinted at. Language hardens, softens, then hardens again. You can watch a movement learning in public.

Nothing about that was meant to last.

Why Their Survival Matters Now

Today, Black Panther Party community newsletters are held in major research collections—often incomplete, sometimes fragile, frequently annotated by previous owners. They are studied not because they are rare objects (many were printed in the tens of thousands), but because so few survived intact.

They remind us that the most valuable historical records are often created unintentionally, by people too busy doing the work to think about posterity.

Ephemera doesn’t just document movements after the fact. It shows us movements while they are happening—messy, hopeful, frightened, determined.

And sometimes, folded into a pocket and forgotten, it waits decades for someone to realize what it has been carrying all along.

Comments