Post #6: “After Hours: The Hidden History of Harlem’s Queer Nightlife”

- andrea0568

- Oct 29, 2025

- 2 min read

The Harlem Renaissance wasn’t just about poetry and jazz—it was also about permission. Between 1920 and 1935, Harlem’s streets pulsed with a kind of creative electricity that didn’t stop when the clubs closed. And if you knew the right door, the real revolution started after hours.

The Clam House on 133rd Street was one such place—run by Gladys Bentley, a tuxedo-wearing blues singer whose deep voice and defiant swagger made her both a legend and a target. At a time when being openly gay or gender-nonconforming was dangerous, Bentley turned every performance into a declaration: here, we are allowed to exist.

These bars and rent parties—half legal, half legend—were the city’s underground sanctuaries. They drew drag kings, poets, musicians, and ordinary people who just wanted to breathe without disguise. Langston Hughes called them “interracial, interclass, and inter-anything you can imagine.” Zora Neale Hurston attended. So did white downtown bohemians slumming uptown for the thrill of transgression.

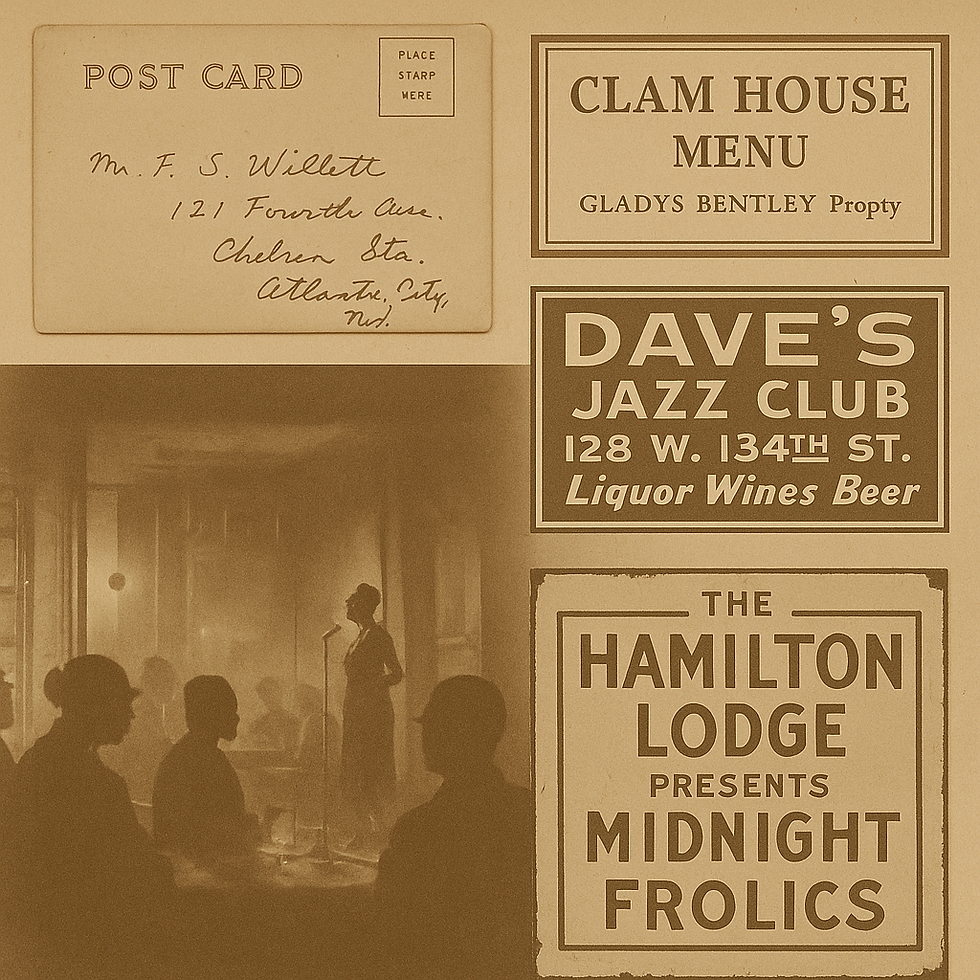

Most of what we know about these spaces survives through ephemera: postcards, party invitations, flyers folded into coat pockets and forgotten for decades. Those scraps are the record of a world too fragile for headlines but too alive to vanish entirely.

When collectors find a flyer from a “drag ball” at Hamilton Lodge or a menu from the Clam House, they’re not just holding paper—they’re holding proof. Proof that joy, identity, and resistance coexisted in the same smoky rooms. Proof that art isn’t just created onstage—it’s lived, nightly, by the people brave enough to show up.

The Renaissance promised a rebirth, but in Harlem’s queer bars, people weren’t just being reborn—they were being seen.

Comments